Demand for diesels still buoyant

The bottom has dropped out of the market for new diesel-engine cars, so it stands to reason that the same must also be true for used cars. If nobody wants a new diesel car, then presumably nobody wants a used one either, leading to a considerable drop in value. That’s certainly what you’ll hear from the self-appointed car expert who sits in the corner of the snug in the Red Lion, but the reality is that his claims are false.

In fact, the exact opposite is true. While sales (and therefore supply) of new diesel cars have significantly decreased, there’s been no let-up in demand on the used market. And as any economics enthusiast will tell you, if you reduce supply but demand stays the same (or increases), a rise in prices is sure to follow.

Diesel cars arrived in the UK in significant numbers in the 1980s, with intensity building in the 1990s. By the turn of the century, diesels were no longer the poor relation, with drivers encouraged to shun petrol in the quest for greater fuel efficiency and fewer CO2 emissions. Accounting for just 19% of new-car sales in 2007, diesels went on to command 56% of the market in 2011. Much of the increase was due to diesel becoming the default choice for company car drivers who wanted to benefit from low benefit-in-kind tax bills, while fleet managers loved the lower fuel costs.

But unfortunately, diesel hid a dirty secret because while the fuel economy is inherently better, the exhaust emissions used to be nothing like as clean. However, just as the tide was turning against diesel towards the end of 2015, the current Euro 6 emissions regulations were coming into force, which forced diesel-engine cars to be virtually as clean as their petrol-engine counterparts. Despite this, we were all told that diesels are dirty, so buyers started to shun them, not recognising the vast advances made in cleaning things up.

Over the past few years, the anti-diesel car agenda has gathered momentum, and now consumers have no idea which way to go when buying a new car. An increasing number are opting for an electric car or a plug-in hybrid, and for many people, that’s a great choice. But for a lot of high-mileage drivers, diesel makes the most sense. Yet just 261,772 diesel-engine cars were registered in the UK in 2020, compared with 581,772 in 2019. Admittedly the pandemic skewed things somewhat last year in terms of the number of new cars sold overall, but to put things into perspective, diesels accounted for 31.5% of the market in 2018, 25.2% in 2019, and a mere 16% in 2020.

A couple of years ago, we published a blog on whether or not you should buy a new diesel car, which was swiftly followed by one on whether or not you should buy a used diesel. Our advice remains evergreen, but it’s important to note the supply of decent second-hand diesel-engine cars has reduced further.

Some of this is down to buyers shunning diesel because the received wisdom is that the fuel is bad, but a big part of it is down to car manufacturers dropping diesel options from their ranges. According to an Autocar article, new-car buyers had 493 different diesel cars to choose from in November 2015, and five years on that had dropped to just 267 — with many of those on borrowed time.

The reality is that few new cars are sold as such. More than 80% of private buyers sign up to a PCP, so they’re just committing to a monthly charge for three or four years. Most company cars are leased, so those fuelling the new-car market don’t have to worry about long-term running costs or reliability. They’ll run the car only while it’s in warranty and they can afford to have the latest technology. But those buying used aren’t always in such a fortunate position. Low running costs are often more important, which means no expensive battery packs to replace, along with the best possible fuel economy. Hence the lack of appetite for electrified cars, but a more significant demand for diesels (and petrols, too).

What’s important to bear in mind is that there are regional differences around demand. Those in rural areas have a greater appetite for ICE (internal combustion engine) cars than those in urban settings, especially if there’s a Clean Air Zone in place. At HPI, we expect demand for diesel cars to remain healthy compared with supply, unless there is a significant change in government legislation.

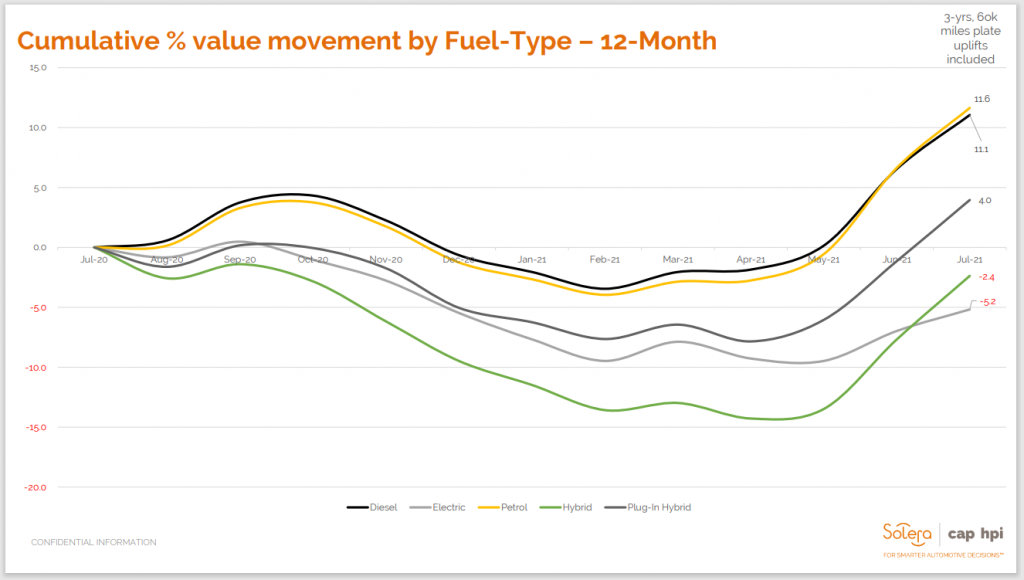

The graph here shows how the value of used diesel cars has increased over the last year, in line with petrol cars. Thanks to strong demand in the used car market overall, diesel values increased by an average of 11.1% over the year. In contrast, petrol-engine cars performed even more impressively, with an average increase in value of 11.6%. Meanwhile, electrified cars (electric cars and hybrids) have not held their value so well; they dropped in value considerably for a while but have recently started to recover.

Taking July 2020 as our starting point, values of petrol- and diesel-engine cars rose by almost 5% over the next three months, whereas electric and plug-in hybrid models initially stayed nearly static before falling away quite sharply. Hybrids performed the worst of all and continued to do so until the last few weeks when they started to recover, overtaking electric cars in the process. Compared with a year ago, the only electrified cars that have seen any gain in average values are plug-in hybrids, which are up by 4%, whereas hybrids are typically down by 2.4%. Coincidentally, electric cars have dropped by 5.2%.

Part of the reason for the lack of enthusiasm for used electric vehicles (EV) and hybrids is the high purchase cost; electrified cars tend to be significantly more expensive to buy than an equivalent petrol- or diesel-powered model.

Many consumers still don’t feel confident that they know enough about the technology. When purchasing an electric vehicle, they often ask themselves the following:

- Is it reliable?

- Is the charging infrastructure good enough yet?

- Will the batteries go flat, leaving me stranded?

Many of these potential buyers aren’t able to charge at home, which significantly reduces convenience. One in three car owners has no home-based charging station.

Despite this, an increasing number of new car sales are of electrified models, with diesels continuing to decline. What will be interesting to see is whether car buyers latch on to electrification as quickly as the government would like, leading to a rise in used values of such cars, or whether values will continue to fall, with the market becoming oversupplied with hybrids, plug-in hybrids, and EVs. If buyers continue to prefer petrol- and diesel-engine cars, will their values on the used market continue to rise, forcing the self-proclaimed expert in the Red Lion to change his tune?

Richard Dredge

July 2021